Information from Gary Buerman and Darrell Vasseur

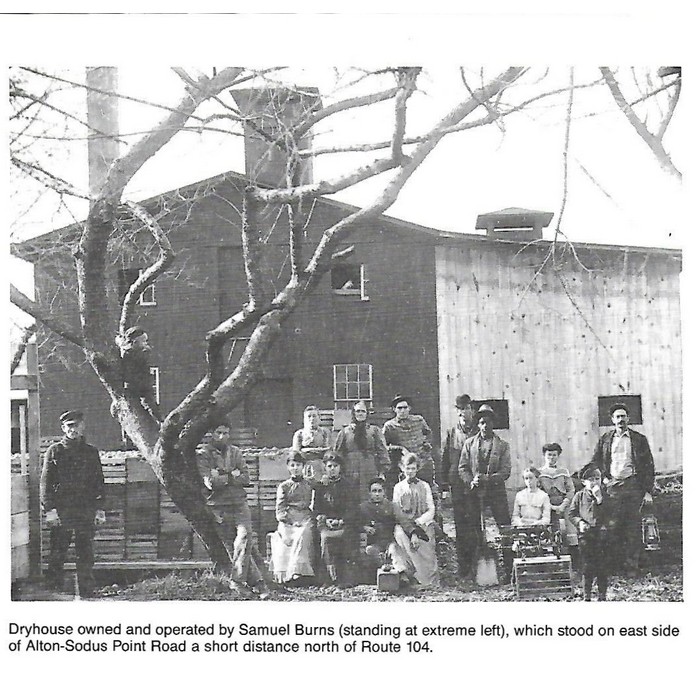

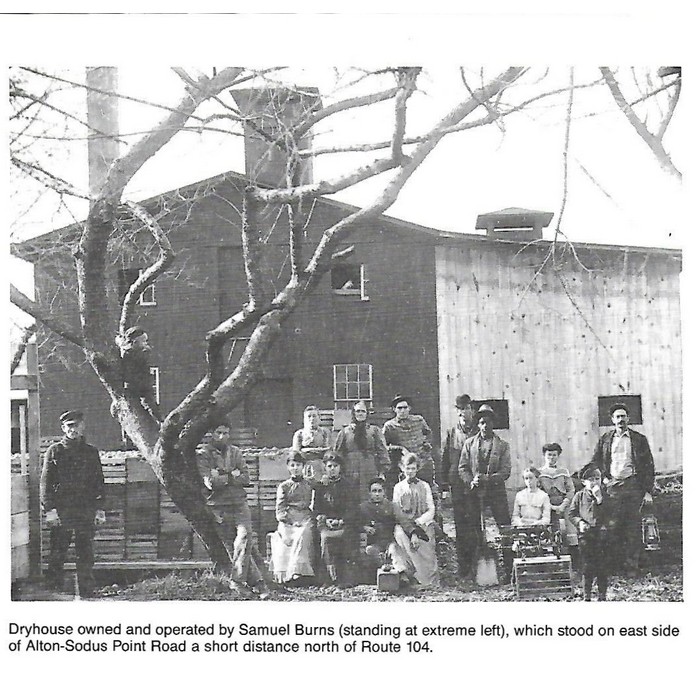

Darrell Vasseur sent me a note on the Apple Dry Houses in Alton. There were at least two commercial apple dry houses in Alton. Besides the Burn’s dry house(pictured above) there was a second dry house where the Continental Can building was built. This was the site of the Alton Fruit Growers Cooperative Association. Also in Alton, my great-great uncle JM Buerman had a dry house behind his house and there was another private dry house across the road from my parent’s house. This one was torn down about 1962

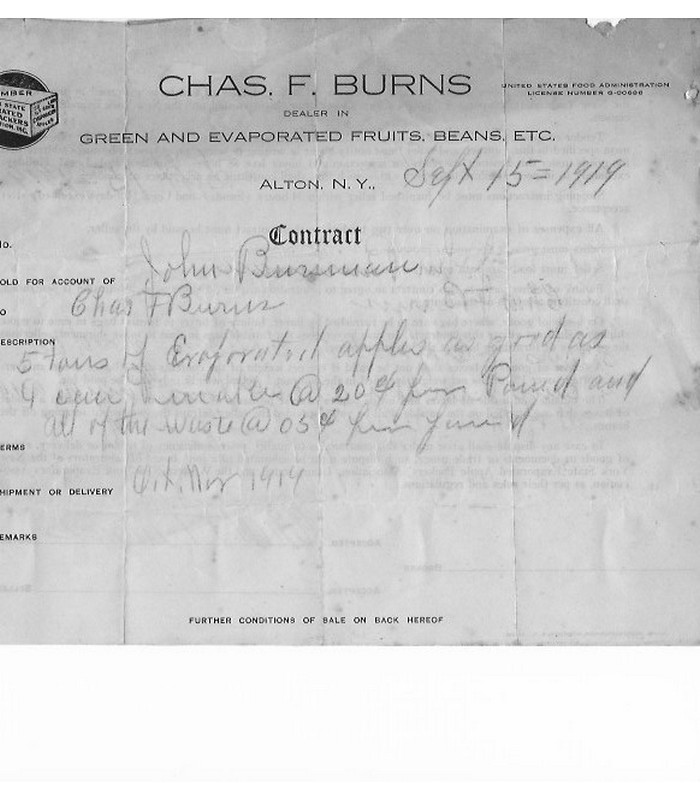

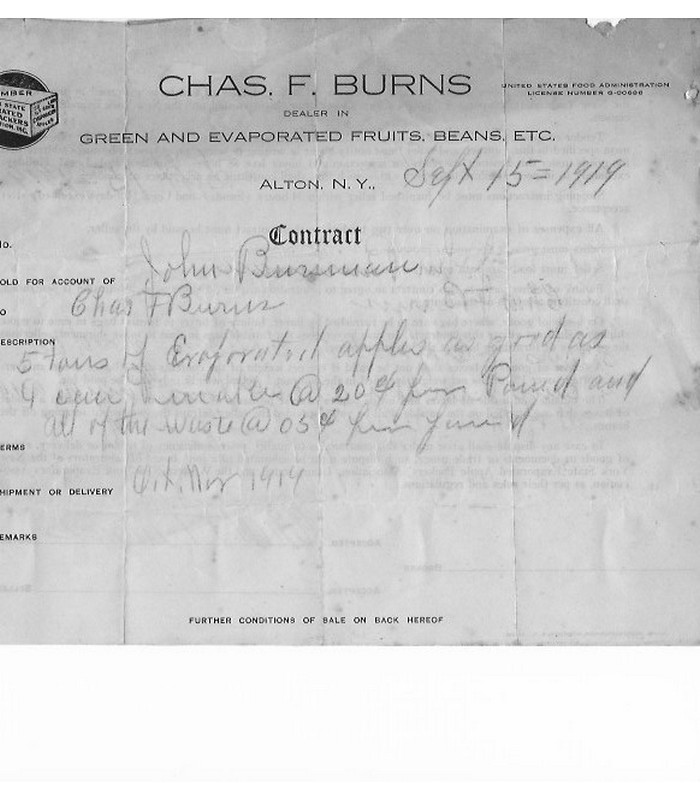

Attached are picture of the deeds from the cooperative and a bill of sale of “evaporated” apples from John Buerman to Chas Burns Sept 15, 1914.

Story from “The Fruit Industry in Wayne County, New York 1823 – 1984 pp 19-22

Story and photo of Samuel Burn’s Dryhouse courtesy of Wayne County Historical Society

Sodus, always a large fruit producing area in Wayne County, developed an important business in the buying, packing and shipping of dried fruits. A handbill dated 1870 and printed to promote the business of four dried fruit dealers in Sodus, urged dryers to produce good quality dried apples and they would receive a fair price and aid the dealers in “establishing a good reputation for our dried fruit in other markets.” Those who produced poor quality dried fruit, half-pared, half-cored and half-dried were reminded that they would receive a low price for their product or as stated in closing — “poor fruit, we do not want at any price.”

In describing Sodus, Mclntosh’s History of Wayne County, New Hark cites further evidence of the important trade in dried and fresh fruits to the area in the 1870s.

Mclntosh noted –

The town is adapted to a mixed husbandry, — grain, stock, and fruit-growing. The latter proves especially successful. Year by year more land is devoted to orcharding than before. The quantity of green apples shipped rivals the most prolific portions of Orleans and Niagara counties, and there is more dried fruit bought from first hands at Sodus village than at any other place of equal size in the world.

The use of dry houses for drying fruit, especially apples, became widespread during the last half of the nineteenth century. In a dry house, five steps are involved in turning fresh apples into dried apples — peeling and coring, trimming, bleaching, slicing or quartering and drying.

Hand-driven and later power-drive peelers were used to remove the peel and the core from the apples.

This photo of an old hand cranked apple peeler is courtesy of Mary Jane Mumby. She and her grand kids still use it to make applesauce.

Larger commercial dry houses as well as smaller farm operations employed both men and women seasonally to process the dried fruit. According to Ward Buhlmann, a retired dry house operator in North Rose, women were employed at his dry house to feed the apples onto the peeling machines.

The peeled apples moved from peelers to trimmers by a conveyor belt or were carried in buckets, depending on the equipment in a dry house. The trimmers, most always women, would remove any pieces of skin or bruised spots before the apples were sent to the bleacher. The bleacher treated the apples with fumes from burning Sulphur or “Brimstone” to keep them from discoloring. They were then sliced into rings or quarters and the drying process was ready to begin.

Most of the dry houses in Wayne County used kiln dryers. The sliced apples were spread out on the kiln floor made of basswood slats placed close together. Space was left between the slats, allowing heat from the furnace below to rise and dry the fruit. The bottom edges of the slats were beveled in order to provide better air circulation. The slats were oiled about once a week with a lubricant such as mineral oil or salt pork to keep the apples from sticking.

The heat to dry the apples was provided by a furnace underneath the kiln floor. Coke was most commonly used to fuel the furnace. Ward Buhlmann remembers that —

coke made a hotter, quicker and faster fire and you could dry more apples with it. Of course we’d melt the furnaces up every year and have to renew the staves and a lot of the grates but it really made heat. It would take about a ton of fuel to dry a ton of apples.

The temperature in the kilns would often rise to 120 degrees. The furnace had to be tended around the clock to keep it hot and to guard against the chance of fire. Since dry houses were made mostly of wood and were exposed to extremes of heat, fires were not uncommon. Ward Buhlmann recalls that —

in the kiln rooms it was so hot that you couldn’t touch the wood. Never had a fire outside of a couple little flare ups. I happened to be right there and see it and squirt the hose on and put it out. But never had one burn down due to the heat of the kiln.

According to Norton Waterman, retired fruit processor in Ontario, dry house fires were “very hot and at times they got away from them. Dry house fires were very common, in fact, it got so it was hard to get insurance for them because so many of them burned down.”

The apples on the kiln floor required periodic turning in order to even the drying process and prevent the fruit from burning. Drying took from fifteen to twenty hours depending on how thick the apples were piled on the kiln floor and how hot the heat was from the fire. Many commercial dry houses operated four to six kilns, often using one for drying the waste, and the others for drying the apples. The peels and cores from the waste kiln were sold to be processed for pectin.

After being removed from the kiln, the dried apples were piled in a curing area where their moisture content would become uniform. Norton Waterman, Whose family was in the dried apple business in the early part of the century, remembers that by law, apples had to be dried so that they contained no more than 24% moisture. Most dry house operators were able to test the dryness of apple slices by feel. Samples were also sent to laboratories in Rochester for analysis.

When the apples were ready to be brought to market from small family-owned country dry houses, they were placed in cloth bags and brought to middlemen. These middlemen then packed the apples in twenty-five or fifty pound boxes and in turn sold them to dealers and exporters. Many dried apples were exported to Europe where fruit was not so plentiful. Dried fruits were easily shipped without harm from cold and took a fraction of the space needed for barrels of fresh fruit.

Drying continued to be a major method for preserving fruit in the County until the 1920s. With the introduction of cold storage in the early twentieth century, the increase in canning factories in the County and a decrease in the exporting of dried apples to Europe, the market for dried fruits was diminishing. However, a few dry houses continued to operate as late as the 1950s and many County residents living today have vivid memories of working in them.