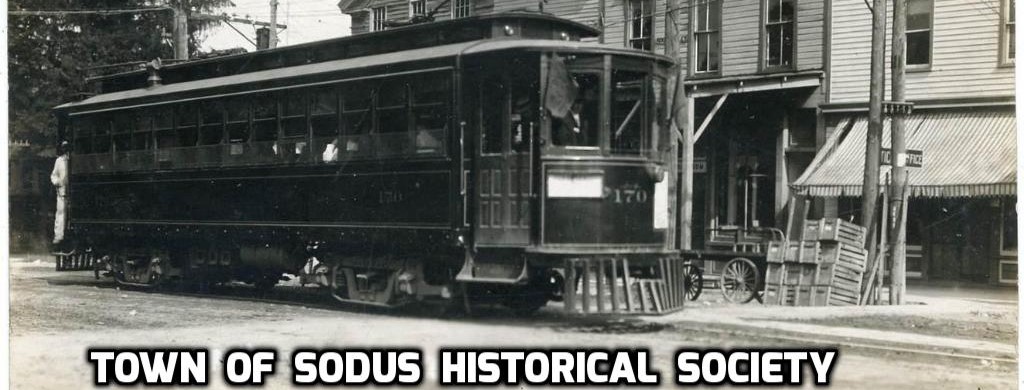

Photo courtesy of the Town of Sodus Historical Society. Information courtesy of Sandy Hopkins

This photo depicts the three accused murderers (Ed Kelly, Frederick Schultz and James McCormick) of Edward Pullman being transported to the old Sodus Opera House on the trolley for a hearing before Peace Justice Herman Kelly. Edward Pullman was a constable and night watchman who was killed on March 23, 1906 while making his rounds at the K. Knapp’s Bank where the hardware store is presently located in Sodus. This photo was taken on April 11, 1906.

Three murder suspects left to right: Fred Schultz, James McCormick and “Big Ed” Kelly

The following information was obtained from the March 19th, 1944 edition of the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle:

Violence Feared as Mob Closed In on Members of Ed Kelly Gang

By Arch Merrill

The crowds started pouring into Sodus village at break of day. Farmers came in Democrat wagons, in buggies, in surreys, a few on horseback, over roads that were deep in mire for it was April in the year 1906, of the pre-paved road era.Trains of the Rome , Watertown and Ogdensburg Railroad brought hundreds more. So did the inter-urban trolleys of the Rochester and Sodus Bay line. People came from Oswego, from Rochester, from Lyons, from every point of the compass. At 8 o’clock the sidewalks were jammed with the greatest crowd in Sodus history. There was more than a hint of spring in the air. Buds were beginning to form on the trees, heralds of the blossoms that soon would scent all the rich orchard land along the lake. But it was no gay spring festival, no rural Mardi Gras that had brought three thousands to Sodus. The show was a grim and morbid one.

A fortnight before, Edward Pullman, the village watchman, had been shot to death by yeggs he discovered at work in the Knapp private bank. The criminals had fled in stolen cutters. Three suspects had been rounded up the same day in a Rochester rooming house. Two others escaped. Police identified the trio held as notorious yeggs; Big Ed Kelly, Frederick Schultz and James McCormick. At first public wrath was so intense that the prisoners were housed in the Monroe County Jail. Later they were transferred to Lyons, county seat of Wayne. Although it was the heyday of the safe blowers and their Nemeses, the Pinkerton Detective Agency, bank robberies and killings were rare sensations in the countryside along the Ridge. So when on April 11, 1906, the stage for a hearing for the three men, charged with murder, was set in the old Sodus Opera House before Peace Justice Herman L. Kelly, some 3,000 persons were milling about the streets of Sodus long before the prisoners arrived.

A detail of six officers brought them by train from Lyons to Wallington, whence they boarded an interurban (trolley) for Sodus. In charge was Sheriff Yeomans. His chief lieutenant was Deputy Jeremiah Collins. By mistake they were dumped in front of the Snider Hotel, some distance from the Opera House. Immediately prisoners and guards were surrounded by a mob of 2,000. It was a tense moment. The prisoners, tough characters though they were, quailed. Then 20 special deputies swung into action and cleared a path for them through the crowd. Women and children were trampled. Some were carried as if on an ocean wave into the impromptu courtroom. The doors were locked and hundreds of disappointed sensation seekers were left outside. The legal proceedings were routine, an examination which resulted in holding the men for trial. But the air was surcharged with drama. Every neck in the room craned to get a glimpse of the prisoners. No actor who had trod the board of the old Opera House ever had a more attentive audience. They saw a big, broad shouldered, poker faced man who might have passed for a city alderman or a corner saloon keeper. That was Big Ed, the leader. The second man was a younger, slimmer, but just as imperturbable chap who walked with a slight limp. Fred Schultz had a bullet wound in his leg, a memento of Ed. Pullman’s bravery. The third, James McCormick, was hook nosed, nondescript in appearance, but with a long record as a safe blower. A murmur ran through the crowd as a middle- aged woman in black took the stand. She was dry eyed, stony, calm in her grief. She gave the three manacled men a long, searching look. Women put their handkerchiefs to their eyes. The woman in black was the widow of the slain officer. John J. McInerney, young, aggressive, confident, appeared as counsel for the trio. The mills of justice ground on without further drama. The crowd relaxed and its curiosity sated, allowed the yeggs to return in peace to their cells in Lyons jail. McInerney sought and won separate trials for his clients. He also obtained a change of venue from Wayne to Monroe County. It was nearly a year before the first of the trio faced a jury.

While the prisoners were in Lyons jail word came to the authorities that friends on the outside were planning a delivery. The trio was hastily transferred to the old red brick jail in Rochester’s Exchange Street. They had been there less than a week when one night Jailer John Birdsall, in making his rounds, found the lock on Schultz’s cell had been tampered with. Schultz was searched and on his person were found several small diamond saws. On Kelly were found more saws, a scissors blade used to sharpen them and some twisted wire that might come in handy for picking locks. On McCormick the officers found nothing. Possibly he was to be left behind. Iron bars were found to have been sawed through and plastered into place by soap and dust. After that Sheriff Bill Craig ordered a close watch kept on every movement of the trio. The accused took this defeat philosophically. Big Ed would talk freely with reports – about the weather or politics – but when the questions swung around to himself or his activities, he closed up like a clam and his steel gray, seemingly frank eyes narrowed. That year the newspapers in the nation were full of the sensational murder in New York’s Madison Square Garden of Stanford White, the noted architect, by Harry Thaw, a gilded playboy. But in Western New York the impending trial of the Sodus bank robbers overshadowed the Thaw case.

The Schultz trial opened in February, 1907. It was the first of three dramatic court room battles. The opposing legal gladiators were resourceful men. To aid Wayne County District Attorney Joseph Gilbert in the prosecution, the state had called upon George Raines, a Titan of the Rochester bar, with 40 years’ experience, a former senator, a man of commanding skill. His opponent was young “Jack” McInerney, admitted to the bar only four years before, and bent on winning new laurels on this spot-lighted stage. The trial drew packed houses, with many women in the crowds. The fight was bitter from the picking of the first juror to the verdict of the last trial. One of the jurors in the Schultz case was the Rev. Clarence A. Barbour, then pastor of Lake Avenue Baptist Church, later to become president of the Rochester Theological Seminary and of Brown University. The defense was in the main, an elaborate alibi. McInerney used every trick in his bag to discredit the state witnesses. The Pinkerton agency had sent their men to Rochester to help gather evidence. McInerney charged they had intimidated witnesses. Contradictory evidence among the police officers helped the defense case. Lawyer McInerney cross examined his own brother, Policeman McInerney, who had helped capture the prisoners, as if he were a total stranger. Raines marshalled all his evidence – the tell- tale horse hairs on the men’s clothing, the map of the Sodus area found in their room, the guns and the safe cracking tools. He brought out witnesses who claimed to have seen the three men driving furiously in a horse-drawn cutter toward Rochester the morning of the murder. He stressed the police records of the accused. It was contended that the bullet that killed Pullman came from Schultz’s gun. The summations were master-pieces. Raines rose to the heights of old fashioned oratory. McInerney talked in a calm, persuasive tone – to the jury alone. The graduating class of School 23 visited the court to hear the summations. After nearly two months of hearing evidence, a jury found Schultz guilty of murder in the second degree. He had escaped the electric chair. Throughout the trial, the defendant had been pale and impassive. He had chatted gaily with the young son of Jerry Collins, the new sheriff of Wayne County, who had brought him red apples from the country. But when the presiding Supreme Court justice, Arthur E. Sutherland asked Schultz if he had anything to say before sentence was pronounced, the yeggman dropped his mask of nonchalance and launched into a bitter denunciation of unnamed persons whom he accused of treachery. Judge Sutherland halted the harangue to sentence Frederick Schultz to a life term in state’s prison.

The trial of Big Ed Kelly followed closely on the Schultz conviction. The evidence was much the same but crowds flocked to the Court House because Kelly was the most notorious and most colorful of the gang. They delighted in a heated verbal clash, marked by pungent expletives, between the burly defendant and Jerry Collins. And the rival barristers, Raines and McInerney, fought bitterly, just as they had in the previous trial. The verdict was the same as in the Schultz case. So was the sentence. But before he was sentenced, Big Ed also made a speech. He called Justice Sutherland “the thirteenth “juror” and termed his charge to the jury “a summation for the prosecution.” The dignified jurist ignored the tirade. When Big Ed was taken to Auburn Prison, a crowd gathered at the gates and fought for a half- smoked cigar he tossed away, as later mobs were to scramble for a baseball autographed by Babe Ruth. The McCormick trial was a lesser show. This yegg was smaller fry. The twice- told tales were told again from the witness stand but public interest had waned. The highlight was the appearance of Robert A. Pinkerton, head of the great detective agency, majestic in sweeping mustaches. He identified McCormick as a much- wanted Toledo safe blower also known as Henry King. McCormick was convicted of second degree manslaughter and sentenced to 19 years and nine months in Auburn. He made no speeches on hearing his sentence pronounced.

Prison bars did not hold Big Ed Kelly for long. Rochester read within a few years that he had escaped. Tourists later told of seeing him near Paris, France, where he was operating a cafe. Maybe that is only legend of a case of mistaken identity. But Ed was never caught. Schultz was freed after serving 20 years of his sentence. His name appears again in Bill McInerney’s fat scrap book under date of 1929. Schultz then was arrested in New York for carrying concealed weapons and violating his parole. The Rochester detective was called to New York to testify against the yegg. So again the pair met 23 years after that first encounter in a Big B Place rooming house. Schultz “beat the rap” in New York, maybe because his lawyer was the clever Samuel S. Lebowitz. What happened to McCormick after his prison term is unknown. Possibly all the defendants have been called to a higher Tribunal than the courts of New York State. Many of the principals in this drama of the Horse and Cutter Days are gone from this vale of tears. Bill McInerney is retired. But he still had his bulky scrapbook and his memories of the manhunts of yesteryear.